By Dr. Sam Eno

ABSTRACT

The Nigerian state continues to grapple with centrifugal forces of ethnicity, religion, and regional allegiance. These challenges threaten the foundations of national unity and impede the realization of a stable federation. This article proposes a bold, radical, and pragmatic reconfiguration of Nigeria’s political structure. It explores alternative nomenclatures for the six geo-political regions, enhanced regional autonomy, devolution of powers, and cost-effective governance models. By drawing on comparative global examples, the paper argues that such reforms would not only preserve Nigeria’s unity but also create an efficient, economically sustainable, and forward-looking federation.

INTRODUCTION

The history of Nigeria since independence in 1960 has been a history of managing diversity. From the First Republic to the current Fourth Republic, ethnic, cultural, and regional cleavages have remained persistent fault lines. Attempts at centralization have neither stemmed secessionist agitations nor quelled mutual suspicions between regions. Rather, they have intensified competition for federal power and resources, producing a dysfunctional center and dependent peripheries.

To preserve Nigeria’s unity, a more radical yet inclusive restructuring is necessary, one that promotes equity, reduces the cost of governance, and enhances the capacity of federating units. This article proposes a new institutional architecture that prioritizes functional federalism, regional empowerment, and non-divisive identities.

RETHINKING REGIONAL NOMENCLATURE

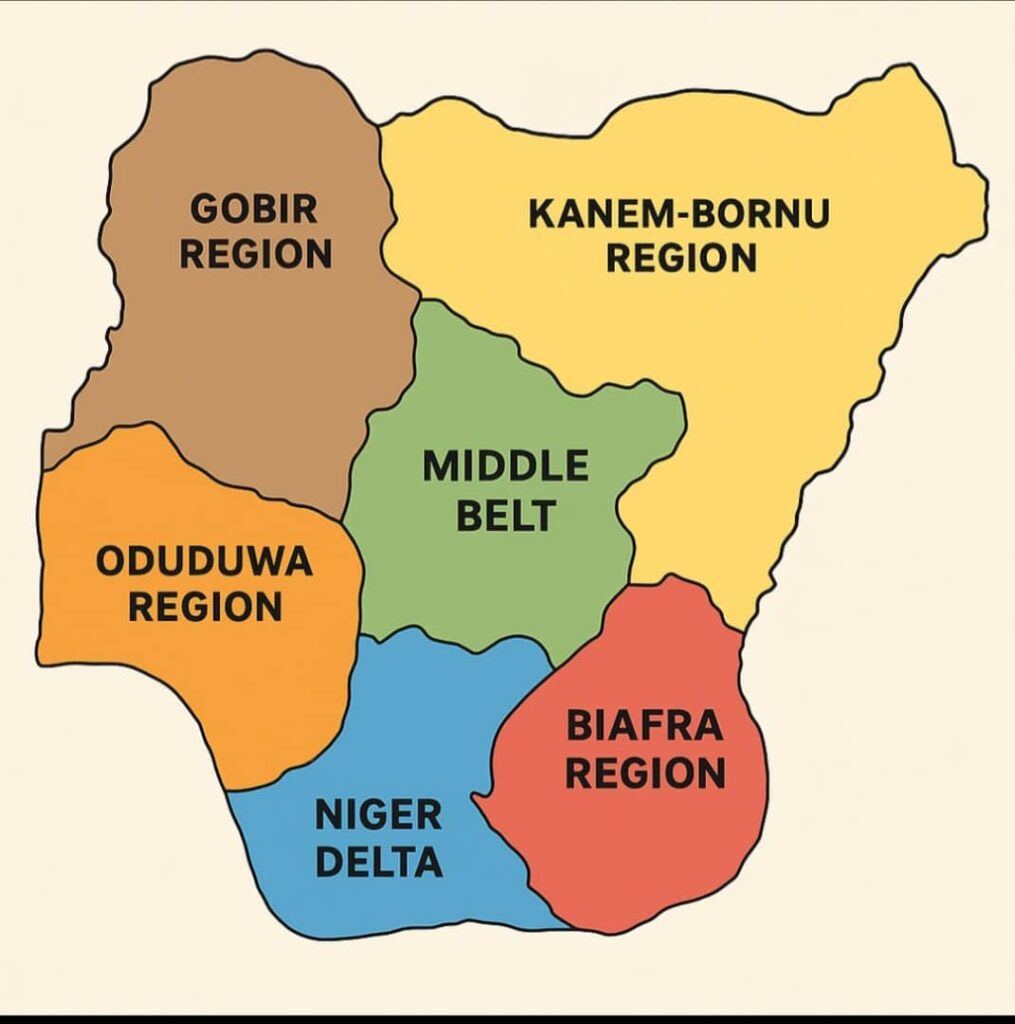

The existing geopolitical zones—North-West, North-East, North-Central, South-West, South-East, and South-South—carry divisive undertones rooted in colonial cartography and ethnic politics. A renaming exercise, therefore, would symbolically decolonize the polity and foster a sense of collective ownership. The following proposed names draw from historical, cultural, and geographical identities rather than ethnopolitical dichotomies:

North-West → Gorbi Region

North-East → Kanem-Bornu Region

North-Central → Middle Belt Region

South-West → Oduduwa Region

South-East → Biafra Region

South-South → Niger Delta Region

By replacing cardinal and ethnically loaded nomenclature with historically grounded but non-divisive identities, the framework for national allegiance becomes less about geography and more about shared heritage. India’s renaming of states along linguistic and cultural lines in the mid-20th century offers a precedent; it reduced secessionist tensions and reinforced federal stability.

POLITICAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE RECONFIGURATION

The reimagined Nigerian federation would rest on three tiers: regions, states, and provinces. Powerful Regional Premiers would oversee development and security, akin to the Canadian model of strong provinces or the German Länder.

State Governors would administer internal affairs while collaborating with premiers for regional strategies.

Provinces (based on senatorial districts) would be led by provincial ministers, ensuring localized representation and administration.

Local Government Councils would remain closest to the people, but with increased autonomy to enhance service delivery.

This layered structure promotes subsidiarity, which is the principle that governance should be exercised at the lowest effective level, enhancing responsiveness and accountability.

Reducing the Central Government’s Powers:

The excessive concentration of power at the federal level has been Nigeria’s Achilles’ heel. A lean central government should retain only strategic functions:

Immigration, customs, foreign affairs, defense, and monetary policy.

Military leadership must rotate regionally with proportional representation to address perceptions of domination.

All other responsibilities,education, healthcare, policing, agriculture, infrastructure, and energy, would devolve to the regions. The United States federal model, where states wield considerable control over internal affairs, demonstrates the efficiency of such arrangements.

Political Rotation and Presidency:

The presidency should be rotational among the six regions for a single, non-renewable four-year term. This limits the personalization of power, reduces cut-throat political competition, and enhances inclusivity. Mexico’s sexenio (one-term presidency) demonstrates how institutionalized term limits can prevent entrenched political dynasties.

Economic Sustainability and Regionalc Development:

Devolving resource control and development functions to regions would stimulate healthy competition. Each region would optimize its comparative advantage:

Niger Delta Region in petroleum and maritime trade.

Oduduwa Region in finance, technology, and agro-processing.

Middle Belt Region in solid minerals and agriculture.

Kanem-Bornu Region in renewable energy and livestock.

Gorbi Region in textiles, agriculture, and commerce.

Biafra Region in industrial manufacturing and human capital.

The model echoes Brazil’s federated states, where decentralized economic planning fosters localized innovation and efficiency.

Cost Reduction in Governance:

To tackle the unsustainable cost of governance, reforms must be radical:

UNICAMERAL LEGISLATURE: The National Assembly should consist solely of part-time senators. Their compensation should not exceed the equivalent of federal permanent secretaries.

Pruned Federal Cabinet: Ministries should be capped and streamlined, following Singapore’s lean but efficient model.

DECENTRALIZED SERVICE DELIVERY: Reducing bureaucratic overlap across federal and regional institutions will save resources.

REGIONAL AND NATIONAL CAPITALS

Strategically locating regional capitals will distribute development and reduce congestion:

Gorbi – Kaduna

Kanem-Bornu – Maiduguri

Middle Belt – Jos

Niger Delta – Calabar

Oduduwa – Ibadan

Biafra – Enugu

Abuja – Political capital

Lagos – Commercial capital

This twin-capital model mirrors South Africa’s Pretoria (administrative) and Johannesburg (economic) split, enhancing balance and functionality.

Comparative Global Lessons

Switzerland’s Cantonal System: Small, self-governing units with shared federal responsibilities.

Germany’s Federalism: Strong Länder with fiscal autonomy.

India’s State

REORGANIZATION ACT: Strategic renaming and restructuring that quelled secessionism.

United Arab Emirates: Resource-based federating units with rotational leadership.

These models prove that political re-engineering, when grounded in equity, enhances unity rather than undermines it.

CONCLUSION

Nigeria’s current structure perpetuates rivalry, inefficiency, and fragility. To preserve its unity, Nigeria must embark on an audacious restructuring that aligns political identity with shared heritage, devolves power to regions, reduces the overbearing central government, and introduces inclusive rotational leadership. Beyond symbolism, such reforms would deepen economic sustainability, reduce governance costs, and build a federation where diversity becomes an asset rather than a liability.

The task is urgent and inescapable. Without radical reimagination, Nigeria risks perpetuating its cycles of division. With it, however, the nation can emerge as a truly united federation,resilient, prosperous, and just.

Sam Eno, PhD

Secretary-General

Abi-Yakurr Peoples Assembly